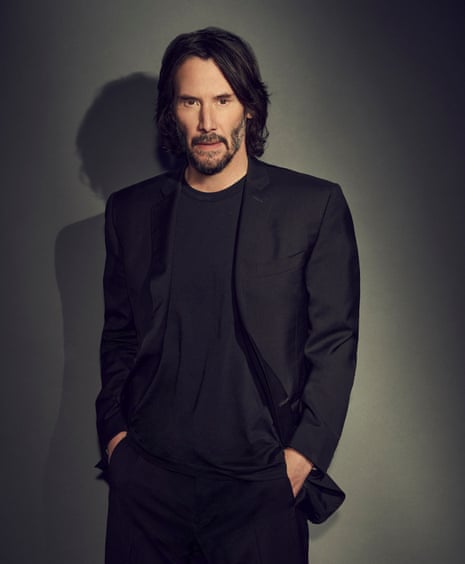

He is one of Hollywood’s hardest working and well-liked actors. As the next instalment of his epic Matrix series hits the big screen, Tom Lamont meets the famously thoughtful star

Keanu Reeves covers his face with both hands. Long bands of the actor’s straggly, jet-black hair flit from side to side as he shakes his cradled head. Reeves, who is 57, has a new Matrix movie out soon. It will be the first instalment in that famous sci-fi series since the turn of the century, when a visually splendid trilogy – The Matrix, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions – shook blockbuster cinema to its foundations. I have just been telling him what an unforgettable outing that first Matrix movie was for me, back in 1999, when I saw it in a packed, noisy cinema full of people who couldn’t sit still for excitement. I’ve also just admitted to Reeves that, when The Matrix Resurrections is made available later this month, via various platforms, I’ll probably stream it at home, probably on a laptop.

I only intend this as a light prompt to get him talking about Hollywood in 2021, a curious time for showbusiness, with Covid precautions and advances in streaming tech combining to make so many movies available for home viewing at the same time as they appear in cinemas. But perhaps Reeves is someone who feels things more deeply than most, because suddenly he begins to plead with me, through muffling fingers: “Dude? Don’t stream that movie… Don’t you fucking stream that movie.”

This conversation is taking place on Zoom, across a few time zones – it’s evening in my London and morning in his Los Angeles. By his own admission, he is not a morning person. As a young actor he’d tell his agents that if they wanted him to get a part, they must not send him to auditions before 11am. I note, today, that we’re talking at 10am Pacific. Adding to his slightly frayed-seeming vibe, Reeves has only just flown back to LA after a film shoot in Paris. Jet lag woke him at 6am this morning. He drank a coffee, ate a banana, smoked an American Spirit Blue and got dressed in his habitual black T-shirt, black denim and black boots. Now he’s on a Zoom call with me, staring out from between his hands and asking: “What are you, crazy? You’re going to stream the new Matrix on a laptop?

His harangue continues, getting louder (“My GOD, man”)and more eccentric (“I’m about to book a cinema for you, Thomas”) until some subtle, delicious shimmer behind his eyes lets me know that Reeves is teasing and has been all along. His hair sticks out at funny angles after all he’s pulled at it. He pats his knees, smiles, and says mildly: “I mean, sure, stream it if you have to.”

I lay this out in detail to illustrate Reeves’s mode of expressing himself, which is eccentric, blasts of silliness mixed with seriousness, and not at all similar to any other famous person I’ve spoken to. He has a facility for poker-faced Canadian irony (he grew up in Toronto) and a mannerly reserve that he assumes is a part of his inheritance from his mum (she grew up in Hampshire). “I think there’s an English formality my mom carries, and that’s become a part of me, too,” he says. Friends of Reeves have said in the past that he is a listener first, a talker second, and I recognise in him some of the tricks of the passive conversationalist. He is unsqueamish about letting a silence linger. After statements, he sometimes repeats them to himself in an undertone, as though revisiting the words for possible flaws. Whenever he is asked a question he hasn’t heard before he tends to look into the distance and think for a while before giving a short, firm, well-formed answer.

When I ask him what qualities define a good listener, Reeves stays motionless for so long I assume our Zoom connection has failed. Then he answers: “I think it’s interest and care. I’m interested in whoever I’m speaking to. I care.”

His parents met on a beach in Beirut. This was in the 1960s. They were both freewheeling young travellers. Reeves’s mother, Patricia, had fled England. His father, Samuel, was a Chinese-Hawaiian who hadn’t settled anywhere either. After Reeves was born in 1964 the family moved to Australia. When his parents separated, Patricia took Reeves and his younger siblings to New York and, eventually, Toronto. She worked as a costume designer. “My mom had her atelier,” Reeves recalls, “where I would pick up pins and clean on the weekend for allowance money.” He has said many times that he never had a substantiative relationship with his biological father, but there was a stepfather, Patricia’s second husband Paul Aaron, who played an important role in his introduction to movie-making.

“I believe I was 15? It was my summer holiday from school. And for a parent it’s, like, what do you do with this kid over the summer? I know, we’ll make him a production assistant on a movie!” Aaron was a director who was about to start shooting a schlocky action flick called A Force of One, starring Chuck Norris. (On its German release, the movie was brilliantly renamed Der Bulldozer.) Reeves was taken on as crew. He fetched things. He managed crowds during outdoor shoots. He recalls, with pride, ferrying a Sprite to the Hollywood legend Claudette Colbert. Meanwhile, he tells me, “I was watching the grips, I was watching actors, I was seeing how a film set really works, the call-sheets, the generator, the lights, the lunchtimes.”

A movie is all hands on deck. I love all hands on deck

His main task was to lug buckets of ice to keep all the on-set drinks and snacks cold. When I ask if this role ever felt demeaning, Reeves screws up his face and protests. “Naw, man, I could start lugging ice right now. A movie is all-hands-on-deck. I love all-hands-on-deck.” Indeed, there are many accounts of Reeves’s good-guy attitude on film sets (pictures recently appeared online of him rolling heavy equipment up a hill during the Paris film shoot) and also credible testimonies of his everyday generosity. Secret charitable donations. Rides for stranded strangers. Of Reeves, Sandra Bullock said recently, “I don’t think there’s anyone who has something horrible to say about him.”

After his experience on The Force of One, he says, continuing the story of his youth, he enrolled at a performing arts school in Toronto. “For one year,” he hastens to add. “They didn’t let me back in after the year.” Bad behaviour? I ask. “My line has always been that I had artistic differences with the principal,” he says.

And what’s the truth behind that line?

Reeves frowns. “I was a bit of a handful I guess. I was a ‘Why?’ guy. I was a ‘How come?’ guy.”

By then, Reeves was already booking acting work, both paid (Cornflakes ads) and not (community theatre). “I was living in a friend’s house. I had enough money. I left Toronto when I was 20 and I drove to Hollywood.” He went to auditions in town (doing better in the ones post-11am) and landed a few good supporting roles, notably opposite Dennis Hopper in River’s Edge in 1986. From 1988 he went on a hot streak, accumulating memorable cameos in Dangerous Liaisons and Parenthood and starring alongside his friend Alex Winter in the first of three Bill & Ted comedies.

I ask Reeves about being a “Why?” guy – a “How come?” guy – when you’re also an actor-for-hire. If the need to question authority is in his bones, what has it been like to submit to the will of all-powerful directors?

“As I see it,” he says, “the job is about investigating ‘Why?’, investigating ‘How come?’ You enter into a collaboration with a director to get those answers. When you don’t have an agreement, when you have conflict – and, yeah, there have been situations where my relationship with the director has been at odds, I might have been emotionally immature sometimes, I might have shouted a few ‘Fucks!’ – then it becomes a battle in the editing room. Luckily I’ve only had a couple of those instances. I’m not gonna say the names of those films, by the way.”

Impossible to guess which films he means; he’s made so many. Point Break with Patrick Swayze. My Own Private Idaho with River Phoenix. He was the baddie in Much Ado About Nothing and the studly saviour of Winona Ryder in a Dracula remake. All of the above were crammed into a heady 24-month period between 1991 and 1993.

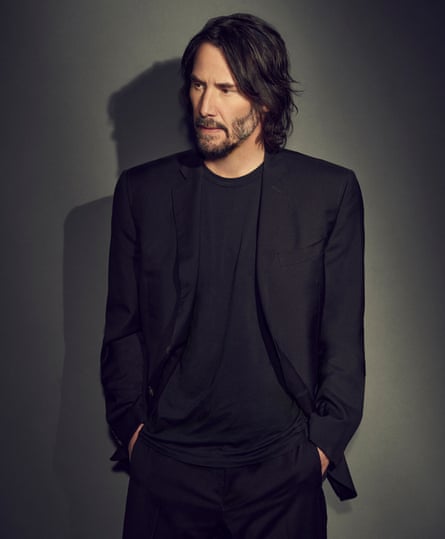

‘I’m interested in whoever I’m speaking to’: Keanu Reeves. Photograph: Brian Bowen Smith

Reeves works a lot. This has often meant his projects overlap, blending at the edges. A few years later, he began his work on the Matrix trilogy, a production that lasted till 2001. The first Matrix was an unqualified hit. It earned £300m in cinemas worldwide, sold record numbers of DVDs, and prompted a story in the New York Times headlined “How The Matrix Changed The Rules for Action Movies.” After that, Reeves went to work on two sequels without much clue what his directors had in mind in terms of the continuing story. Those directors, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, have since suggested the story they told across the trilogy (about finding one’s true identity, resisting suppression and convention) was an allegory of trans experience. Reeves never twigged that at the time. Not many people did. Either way, he’s clearly proud of the work he achieved with the Wachowskis. His feeling is: art belongs to its creators first and foremost. You must do your best to honour their intentions.

I wish he’d been there, two decades ago, to say something wise like this to me after I sat through those two Matrix sequels. My experience of watching them went through phases, first excitement, which turned by increments into panic and boredom, finally becoming a thick and soupy disappointment. In 1999, when I was 17, the first Matrix seemed to me the least boring film ever made. Over and over I guessed what might come next in the story. In 2001, when I was 19, the sequels gave me my first taste of artistic disappointment: how impossible it is for a much-imagined thing to live up to one’s own limitless expectations.

When I tell Reeves this he is sympathetic. The third Star Wars movie was his own big let-down, he says. He was 19 when Return of the Jedi came out. “I went in, like, ‘Wow, I wonder, are they gonna do this, and will they do that…? And then I was, like, ‘Oh no. Oh no.’” Reeves clears his throat. “Um, so I totally get it. I know that experience as a filmgoer. But I just try to let films be, y’know? I try to think about what the creators were going for. It’s their work of art, man. I try to come to their art and meet it wherever it is.”

‘My job is about investigating’: in The Matrix Resurrections. Photograph: Murray Close

This is well expressed, as is Reeves’s lovely description of the passage of time, when he describes the decades of his professional life that came after The Matrix. Each year, he says, seems to slip away that little bit faster than the last, something that always puts him in mind of the turning wheel of an audio tape. “When you’re young,” he says, “you have a big old reel of that tape left, right? And so it appears to revolve slowly. Then, time passes, and there’s less and less tape left on the reel. It spins faster. It spins faster.”

Economic and elegant with his words, Reeves has occasionally put this ability to use by publishing poetry. In 2011 and again in 2016, he collaborated on coffee-table books with the artist Alexandra Grant, lines of his mournful verse appearing alongside Grant’s eerie drawings and photographs. A Hollywood star who takes a risk like this and commits his name to poetry must expect a degree of fascination and even scepticism from the public. Adding to the intrigue of these books, it has since emerged Reeves is in a romantic relationship with Grant. But the way he talks to me about his writing – without shyness but also without bravado –makes it all seem a natural expression of some challenging things he has been through in his life.

Years ago, when Reeves was in his mid-30s, he and his then-girlfriend lost a child in late pregnancy. That girlfriend later died herself in a traffic accident. He has known other bereavements, including the loss of his friend River Phoenix in 1993. (“He was a special person,” he said recently of Phoenix. “So original, unique, smart, talented, fiercely creative. Thoughtful. Brave. And funny. And dark. And light.”) Reeves talks to me in general about grief, explaining that his 2016 book of poems, Shadows, was an effort to externalise it, “contextualise the grief, even be inspired by it, even find a certain pleasure in it… Let [the grief] move, and not be trapped inside it… It just put things in a new shape that I could carry or have with me.”

Was it cathartic, I ask, to revisit those difficult feelings and write them into verse? “Absolutely,” he says.

I ask if there was any emotional cost as well. He thinks for a long, long time before answering, “Yeah. But, hopefully, I have enough in the bank to pay that cost.”

We talk about his work again. In the past decade or so, Reeves says, “I’ve wanted to get as much done as I can before that turning tape runs out… How old am I now,” he asks, rhetorically, “57? Around the time I hit 40, there was this idea of creating more from my artistic loins.” This has meant two or three movies per year, everything from apocalypse blockbusters (2008’s The Day the Earth Stood Still to samurai thrillers (2013’s 47 Ronin) to a comedy in which he voiced an animated cat. In the middle of all this, when he was in his late 40s, Reeves made his directorial debut, a 2013 kung-fu movie, Man of Tai Chi. Busy, busy, busy.

Probably the most significant movie from this part of his career was 2014’s John Wick. An unapologetic fight movie, it was made in collaboration with two of Reeves’s former stunt colleagues from The Matrix, Chad Stahelski and David Leitch. They had a basic concept that proved effective. What if the fights they staged in their film were all limited by what Reeves himself could physically perform? The resulting action sequences had a visceral, haggard, can’t-look-away quality (probably born of a 50-something man absolutely exhausting himself for our viewing pleasure) and John Wick won over an unexpectedly big audience. Reeves says, “I remember thinking, ‘I wonder if the Wachowskis have seen it. I wonder if they liked it.’ I never reached out to ask.”

Certainly the public liked what they saw and John Wick has since spawned two sequels, with more to come in 2022 and 2025. Meanwhile Reeves has circled back to work with at least one of the Wachowski siblings, the coming new Matrix movie directed by Lana.

There’s a story that on the first John Wick, when budgets were tightest, the stunt men and women Reeves fought during those long action sequences would play dead, lie still for a minute, then stand up and scuttle around behind the camera to be killed all over again. It occurs to me, as my conversation with Reeves comes to an end, that his long, strange and meandering career has been a bit like this. Shoot. Shoot. Lie still for a bit. Shoot again.

Before we say goodbye, I remind him of that lovely analogy of his, about the unspooling tape that seems to turn ever quicker. By working so regularly, so relentlessly, has he been trying to slow the turning of time?

Reeves listens to the question gravely, stares to one side while he considers how best to reply, and finally gives the same answer three times. “It doesn’t slow down time. It doesn’t slow down time. It doesn’t slow down time.” The repetition prompts some final thought, and Reeves sighs. “If anything, it speeds everything up.”