Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Dogs have been human companions for a long time, perhaps even longer than we had imagined. Morphological, radiometric, and genetic analysis of bone remains found in the Erralla cave in Spain have revealed that one of Europe’s most ancient domestic dogs lived in the Basque Country 17,000 years ago. The Erralla dog shares the mitochondrial lineage with the few Magdalenian dogs analyzed so far. The origin of this lineage is linked to a period of cold climate coinciding with the Last Glacial Maximum, which occurred in Europe around 22,000 years ago.

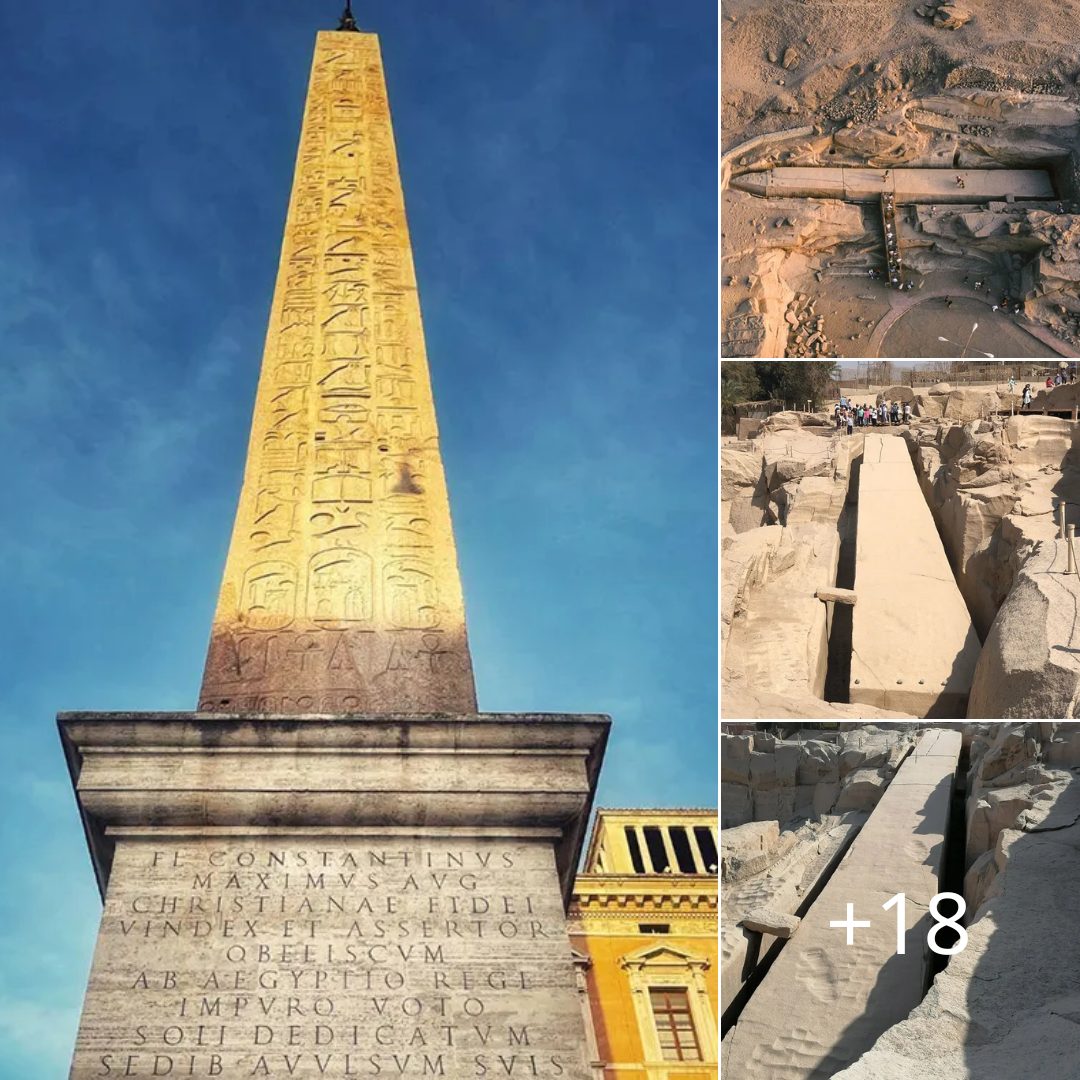

The carvings could be the world’s oldest evidence of dogs wearing leashes. Credit: M.Guagnin et al., Journal of Anthropological Archaeology

In the Chauvet Cave in France, there are extraordinary paintings that are between 20,000 and 30,000 thousand years old. Here, we find what some consider to be the oldest evidence of human-canine relationship.

But what can we learn about the ancient history of dogs by studying DNA? In a groundbreaking study, archaeologists from 10 countries have presented evidence clearly showing that there were different types of dogs more than 11,000 years ago in the period immediately following the Ice Age.

“The research team sequenced ancient DNA from 27 dogs, some of which lived up to nearly 11,000 years ago, across Europe, the Near East, and Siberia.

Scientists discovered that by this point in history, just after the Ice Age and before any other animal had been domesticated, there were already at least five different types of dog with distinct genetic ancestries.” 1

Sometimes, there is confusion, and scientists cannot determine whether ancient carvings were meant to depict wolves or domesticated dogs. The pre-Neolithic rock art found at the sites of Shuwaymis and Jubbah in northwestern Saudi Arabia leaves no room for questions, though. Here, archaeologists discovered dog-assisted hunting strategies from the 7th and possibly the 8th millennium BC, predating the spread of pastoralism. ”

“Though the depicted dogs are reminiscent of the modern Canaan dog, it remains unclear if they were brought to the Arabian Peninsula from the Levant or represent an independent domestication of dogs from Arabian wolves.” 2

One of the most interesting aspects of this archaeological discovery is that the carved lines represent leashes, indicating that the dogs were physically attached to the hunter.

“Particularly notable is the inclusion of leashes on some dogs, the earliest known evidence in prehistory. The leashing of dogs not only shows a high level of control over hunting dogs before the onset of the Neolithic, but also that some dogs performed different hunting tasks than others,” the research team wrote in their study. 2

The rock art demonstrates the importance of dogs to ancient people. Credit: M.Guagnin et al., Journal of Anthropological Archaeology

This means we may be seeing 9,000-year-old engravings of domestic dogs! Before this discovery, the oldest corresponding depictions of dogs on leashes originated from Egypt and are approximately 5,500 years old.

Datings of cave paintings are, however, often associated with great uncertainty, and therefore, it may turn out that the images are “only” 6,000-7,000 years old.

There is scientific evidence dogs were domesticated between 15,000 and 30,000 years ago. Ancient humans valued dogs highly, and there is evidence these animals did not only assist in hunting activities but they also guarded communities and helped to survive in harsh environments.

The discovery of the Bonn-Oberkassel dog buried at approximately age 27–28 weeks, with two adult humans and grave goods, clearly showed how close the human-canine relationship was. Discovered in Germany about a century ago and dating to 14,200 years old, the find is the earliest known deliberate burial of a domestic dog, presumably alongside its owners. In the same burial were also the remains of a second canine.

The puppy died young, but its owners cared for it through sickness. According to the researchers, the owners of these dogs were hunter-gatherers in Germany who treated their dogs not just as resources but also cared for them as pets.

“Since canine distemper has a three-week disease course with very high mortality, the dog must have been perniciously ill during the three disease bouts and between ages 19 and 23 weeks. Survival without intensive human assistance would have been unlikely. Before and during this period, the dog could not have held any utilitarian use to humans.

We suggest that at least some Late Pleistocene humans regarded dogs not just materialistically, but may have developed emotional and caring bonds for their dogs, as reflected by the survival of this dog, quite possibly through human care,” the science team explained in their study.