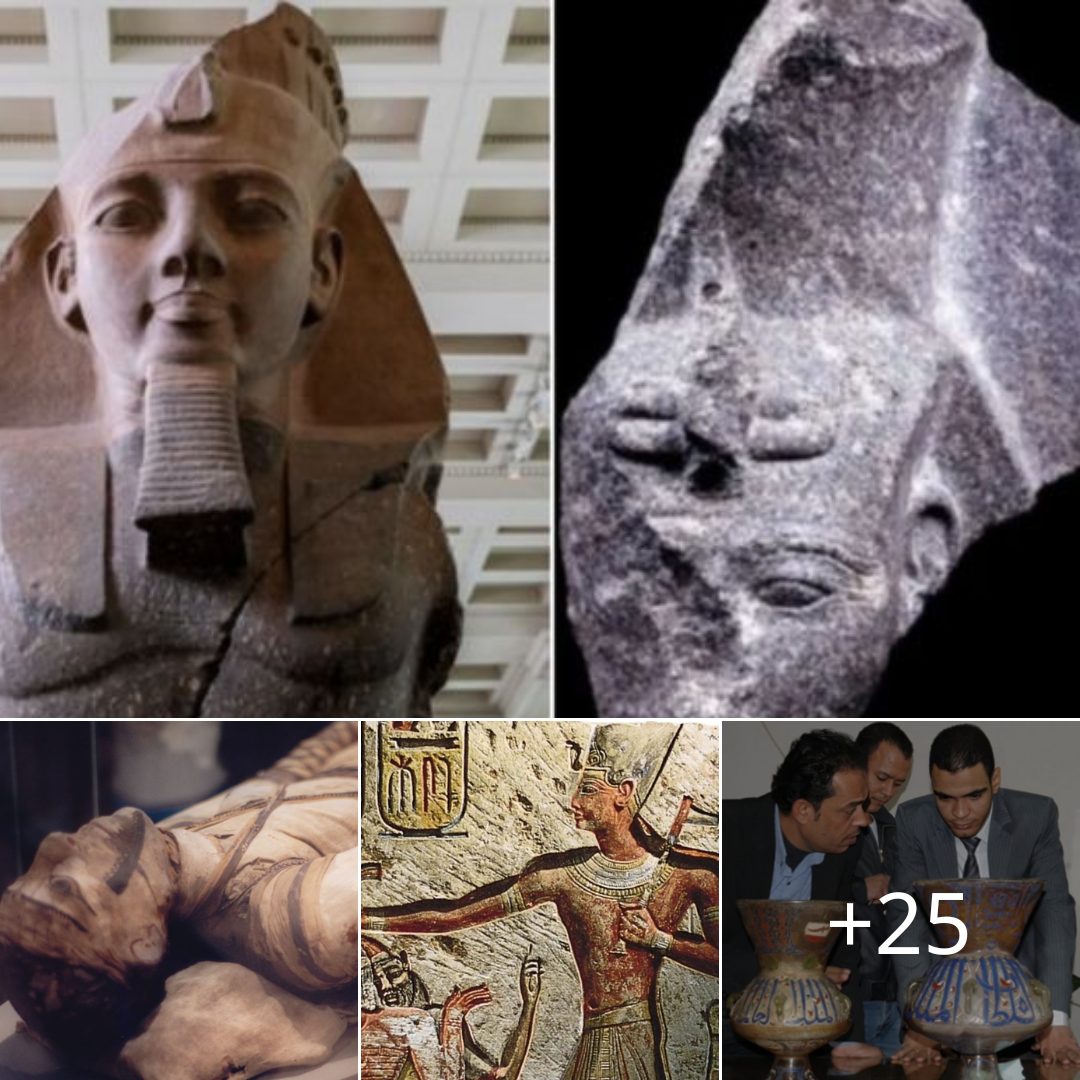

A petroglyph possibly depicting the supernova of A.D. 1006 (star symbol, right of center) and the constellation Scorpius (scorpion symbol, left of center). The boulder on which the petroglyphs appear is located in White Tanks Regional Park, Phoenix, AZ. (Image credit: John Barentine, Apache Point Observatory)

A rock carving discovered in Arizona might depict an ancient star explosion seen by Native Americans a thousand years ago, scientists announced today.

If confirmed, the rock carving, or “petroglyph” would be the only known record in the Americas of the well-known supernova of the year 1006.

The carving was discovered in White Tanks Regional Park just outside Phoenix, in an area believed to have been occupied by a group of Native Americans called the Hohokam from about 500 to 1100 A.D.

The finding is being announced today at the 208th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Calgary, Canada.

Night light

In the spring of 1006, stargazers in Asia, the Middle East and Europe recorded the birth of a “new star” above the southern horizon of the night sky, in the constellation Lupus, just south of Scorpio [simulation].

Unknown to them, what those ancient astronomers were actually witnessing was the swan song of a star as it blew itself apart in a violent explosion called a supernova.

Although nearly invisible today, the supernova of 1006, or SN 1006, was perhaps the brightest stellar event ever to occur in recorded human history. At its peak, the supernova was about the quarter the brightness of the Moon, so radiant that people could have read by its light at midnight, scientists say.

The Hohokam petroglyph depicts symbols of a scorpion and stars that match a model showing the relative positions of the supernova with respect to the constellation Scorpius. The model was created by John Barentine, an astronomer at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico and Gilbert Esquerdo, a research assistant at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona.

“If confirmed, this discovery supports the idea that ancient Native Americans were aware of changes in the night sky and moved to commemorate them in their cultural record,” said Barentine, who studies Southwest archeology as a hobby.

Astronomer by day

Barentine thinks the finding could also help archeologists date other petroglyphs in the Southwest and elsewhere in the world. Dating art made by prehistoric Native Americans has traditionally been difficult because many did not have a written language and shared little in common with the culture and folklore of tribes that came later.

“Quantitative methods such as carbon-14 dating are alternative means to assign ages to works of prehistoric art, but they lack precision of more than a few decades, so any depiction in art that can be fixed to a specific year is extremely valuable,” Barentine said.

A similar petroglyph discovered near Penasco Blanco in Chaco Canyon National Monument, New Mexico is also believed to represent a supernova, but one that occurred later, on July 4, 1054.