In a recent publication, two researchers from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and the Museum of Archaeology of Catalonia have questioned the theory that ancient Iberians only severed the heads of defeated male warriors and skewered them with spikes.

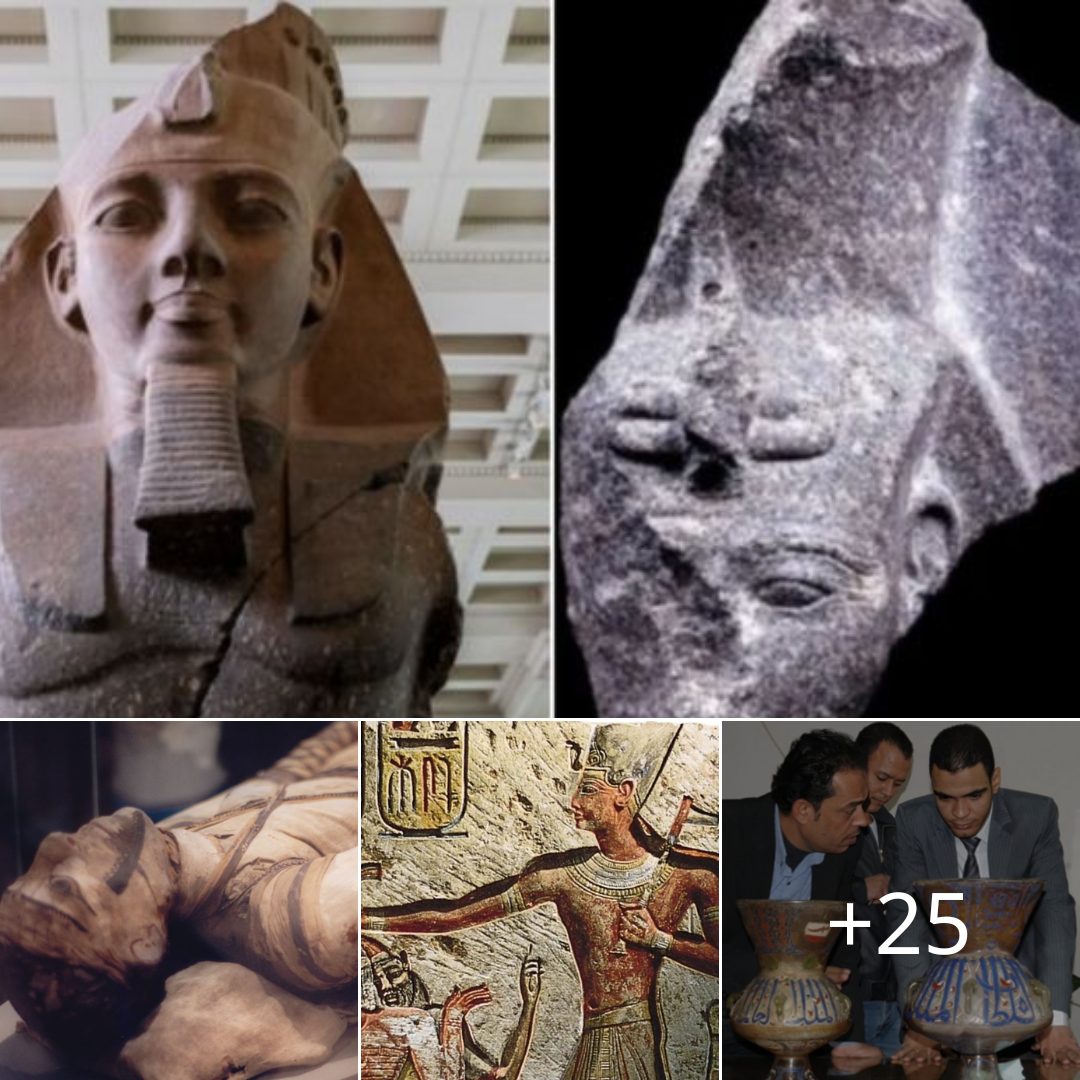

A nailed skull of an Iberian warrior preserved in the National Archaeological Museum[Credit: MAN]

The study, which was published in the journal

Trabajos de Prehistória

, was carried out by Eulàlia Subirà, from the Department of Animal and Plant Biology and Ecology at the UAB, and Carme Rovira Hortalà, from the Museum of Archaeology of Catalonia, based on an exhaustive analysis of the remains of nailed skulls from the Iberian site of Puig Castellar in Santa Coloma de Gramenet (Barcelona), which are preserved at the National Archaeological Museum.The researchers noted that the Iberian peoples (6th and 2nd centuries BC) burned their dead and for this reason “studies of the physical anthropology of their remains are scarce and, as such, of great value”. The remains analysed were found at the beginning of the last century, from 1904 onwards, but, as they point out, “had only been superficially examined”.Subirà and Rovira state that their work provides “significant new results to characterise the Iberian populations, known primarily from classical sources”, adding that “the fact that two of the skulls belong to women and another corresponds to a young man of only 15 years of age questions the theory that assigns the nailed heads exclusively to warriors defeated in battle”.

The Iberians also cut off women’s heads to turn them into trophies[Credit: Subirà & Hortalà, 2019]

When in 1904 the first findings of severed heads were made in the Iberian oppidum of El Puig Castellar in Santa Coloma de Gramenet they were interpreted as “war trophies”. However, according to the scientists, only a small part of them had in fact been examined.

This study presents the results of the anthropological analysis based on their description, age and 𝑠e𝑥 determination, pathological study and marks. The results extend the initial number of individuals from 5 to 12. There are two nailed skulls, three with signs of skinning and several cranial and mandibular fragments with evidence of stab wounds.In addition, they assessed the treatment these skulls had undergone in order to be displayed, providing new significant results that “contributes to the characterization, from the physical point of view, of the largely unknown Iberian populations, in addition to questioning the theory that assigns the severed heads exclusively to warriors defeated in battle on the basis of episodes from the Celtic sphere described by the Graeco-Latin written sources like Poseidonios of Apamea”.

One of the skulls of Puig Castellar, with the hole preparation marks[Credit: Subirà & Hortalà, 2019]

The heads of the individuals, the study points out, were manipulated very soon after their death in order to nail them down and prevent them from shattering (separation of the head from the rest of the body, lifting of the scalp, pre-treatment of soft parts and bone, fixing of the head and drilling).

“This fact indicates that those who performed these procedures posssessed some the anatomical knowledge and used particular tools, such as small fasteners and larger nails than those used in the constructions of the time”.One of the main differences found between the Iberian populations of Puig Castellar and Ullastret is the greater prevalence of a mild form of osteoporosis in the eye cavity among the former group, which “could be associated with nutritional deficiency or some chronic infectious process”.

Fragments of different skulls and jaws found in Santa Coloma de Gramenet[Credit: Subirà & Hortalà, 2019]

The other, equally or more important in the authors’ opinion, is “the greater diversity of the demographic group in the Santa Coloma site, with younger individuals (up to 15 years of age) and a female presence, which does not appear in Ullastret”. The two women identified were adults: one of them, the best known skull, was between 30 and 40 years old when she died; and the other, younger, was between 17 and 25.

The two researchers believe that in order to understand the meaning of the severed heads in Southern Europe during the Middle Iron Age, it is necessary to implement “a thorough investigation that combines physical anthropology with laboratory analysis (DNA, isotopes, residues), the study of historical sources and iconography”.The work conducted by the two scholars sheds some light on the rituals associated with violence in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, starting with the osteological assemblage of Puig Castellar, but the intention is “to go beyond this and contribute to the knowledge of the Iberian population in general,” they said.