Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – In Siberia, there are many interesting stone idols that provide us with valuable history of events taking place in this region of the world. One of the most fascinating statues is the 2,400-year-old Ust-Taseyevsky stone idol that remains shrouded in a veil of mystery.

This stone statue raises several questions scientists are attempting to answer.

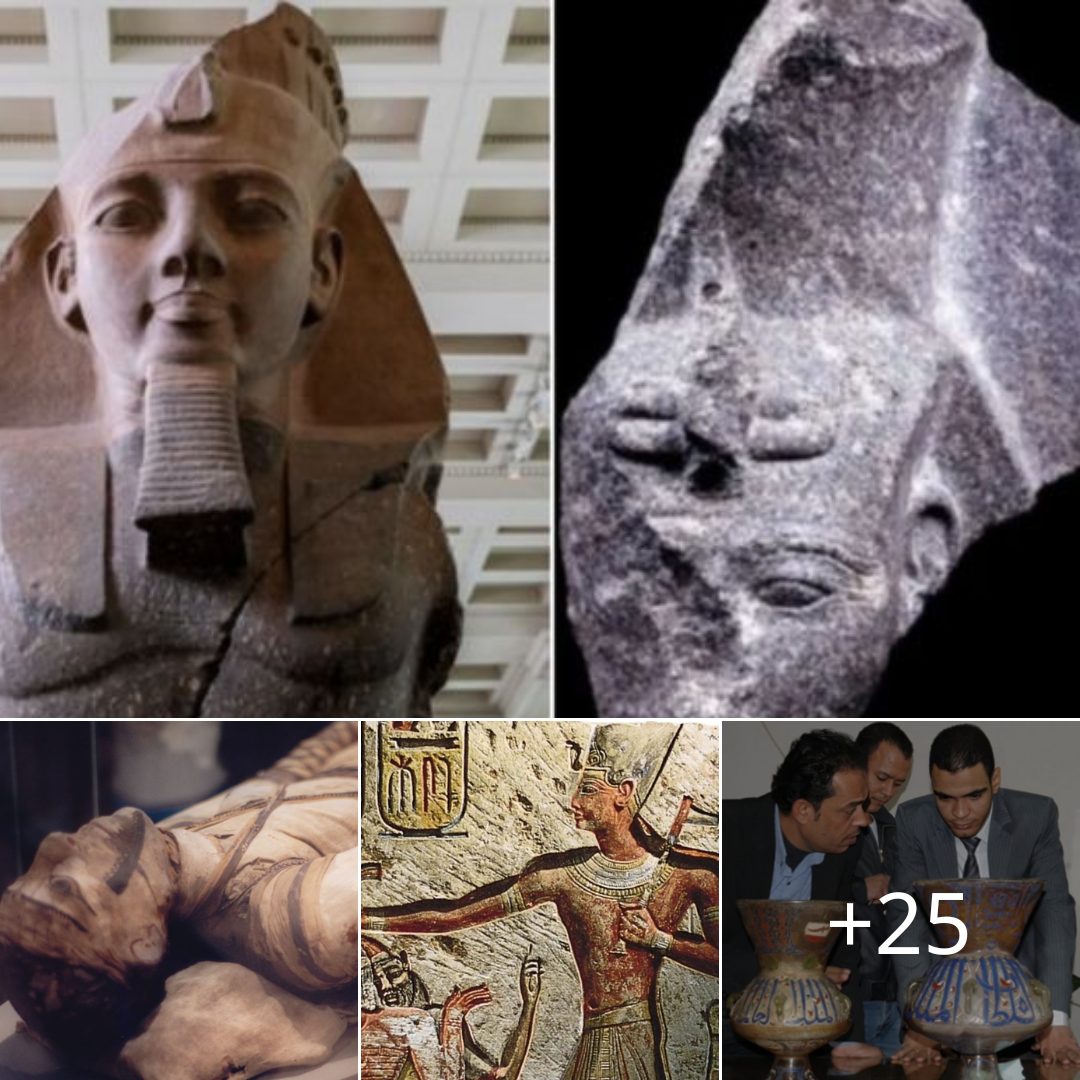

Ust-Taseyevsky stone idol. Credit: Yuri Grevtsov

For example, we must try and figure out why the face of this mysterious stone idol was suddenly changed about 1,500 years ago.

The next puzzle scientists are trying to solve is he had Caucasian features almost two millennia before the Russian conquest of Siberia.

Why Did People Change The Face Of Ust-Taseyevsky Stone Idol?

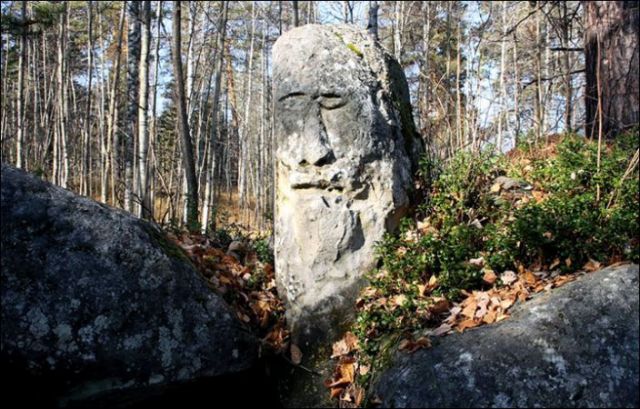

Staring at us from the deep past, the Ust-Taseyevsky stone idol has stood and watched in silence everything around him for at least 2,400 years. He may have stood on the sandstone hill and remained anonymous for much longer if he hadn’t been accidentally discovered in 1975.

“The main stone sculpture visible today shows a man with widely spaced almond-shaped eyes and ocher-colored pupils.

He has a massive nose with flared nostrils, a wide-open mouth, a bushy mustache, and a beard. And yet all is not quite as it seems, for this sculpture, the most northerly of this genre in Asia, underwent a historic version of plastic surgery perhaps 1,500 years ago to give him a less Caucasian and more Asian appearance, according to experts,” The Siberian Times reports.

Credit: Yuri Grevtsov

“Analysis of the sculpture’s micro-relief showed that the original image went through some improvements. The first ‘edition’ was made by knocking, charring and polishing the lines. Most likely it was all made by one person who seemed to have a very strong hand and a good taste.’

Finds of ancient tools, weapons, and bronze mirrors in grottos surrounding the sculpture suggest this and other more weathered and fallen idols were hewn out of the sandstone as a place of worship between the second and fourth century BC.

But in the early Middle Ages a ‘less experienced sculptor’ got to work on the idol and ‘sharply delineated and narrowed the sculpture’s asymmetric eyes. The nose bridge was flattered with several strikes. The nose contour was altered to form ‘two-deep diagonally converging grooves.

The mustache and the beard were partially ‘shaved,“ archeologist Yuri Grevtsov said.

Why would people want to alter the appearance of the Ust-Taseyevsky stone idol changing it from a European look into a more Asian countenance?

Grevtsov thinks the reconstruction was made to make the Ust-Taseyevsky stone idol resemble those who settled in the region.

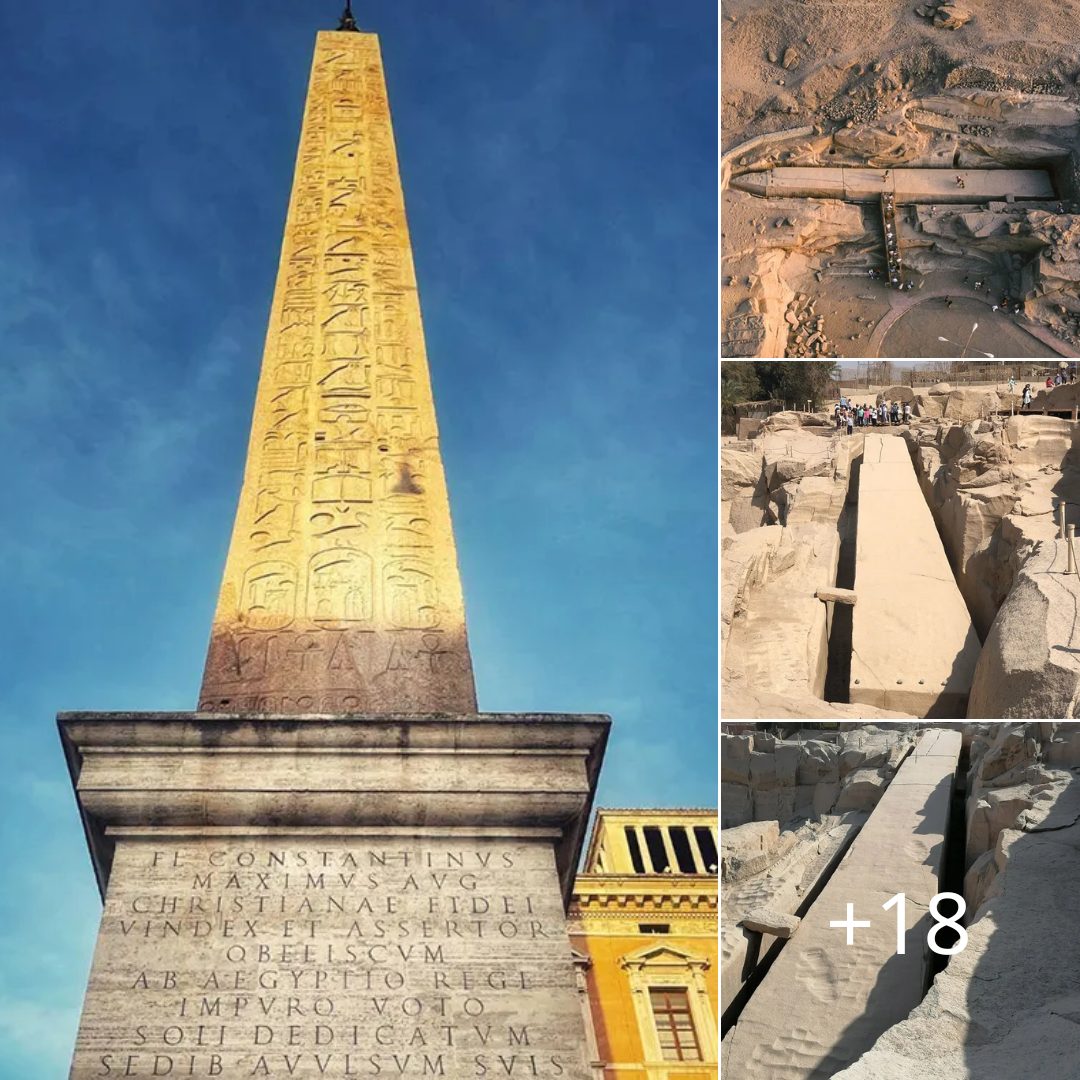

The ust-Taseyevsky ritual site, and the idol. Credit: Yuri Grevtsov, Anna Kravtsova

“Judging by archeological finds found inside the grottos, this anthropomorphic idol was made during the Scythian time.

The first change came when the more European-looking face was transformed to make it appear more Mongoloid was likely to have happened in the early Middle Ages with a shift of the population in the Angara River area,” Grevtsov said.

Scientists also discovered the stone statue was changed once again later. There is a conical hole 1.5 cm in diameter in the sculpture’s mouth. This wasn’t there from the beginning. Obviously, it was drilled later, but why? Could this transformation have occurred with the arrival of Russian people and them introducing the locals to tobacco and pipes?

As Siberian Times writes, “the Russian conquest of Siberia reached this region – in modern-day Krasnoyarsk – in the 17th century.

Senior researcher Grevtsov said the stone idol is the only one of its kind in the taiga so far north: the closest analogs would be 500 kilometers to the south in Khakassia.

Why, though, would the original face has distinctly European features – seen by some as Slavic – when modern-day native Siberian groups have a more Asian appearance?

The answer may be that the Scythian peoples – a large group of Iranian Eurasian nomads who held sway in many Siberian regions at this time – did indeed have this more European visage.

Reconstructions of faces from permafrost burials, for example in the Altai Mountains, shows this to be the case.”

“The rich archeological material found at the site can be divided into five main groups. Weaponry – stone, bone and metal arrowheads, knives and axes; bronze mirrors; harnesses and their decorations; fragments of bear and elk skulls with traces of rituals, for example when their lower jaws were cut off; and ritual elements like a shaman crown made of deer antlers. All the finds bear traces of fire. Given the type, the concentration, and the locations of the finds, we conclude that they were used for ritual purposes. The grottos were sacrificial places where all offerings were buried,” Grevtsov explained.

Ust-Taseyevsky is not the only stone idol in this area. There are other stone statues standing in his close vicinity. Some have somewhat anthropomorphic shapes and others are simply unusual natural formations.

“Some of the rocks collapsed, forming natural constructions with grottos and corridors, and making for a scenic site. In the center of a 22-meter long sandstone ridge, there is a four-meter high rock, which looks a bit like a human profile.’

It was to the left of this that archeologists found two grottos ‘full of archeological finds’.

To the right is the idol with the human face and in front, covered with moss, there was a roughly made petroglyph depicting another human face.

To the right of the human face statue there is another large rock with no traces of human influence yet looking quite like a woman’s head covered with a hood, “Grevtsov tells.

Why Was This Ancient Site Special?

When the Yenisei TV film crew visited the site, they noticed something that could explain why this place was important to ancient people.

“A compass dances frivolously with its needle going as much as 20 degrees off course. Locals also say that the hills act like a magnet to lightning bolts during storms. I wonder if this was the same in earlier times and if people that lived here saw it as a good sign to choose the site for their rituals,” explorer Maksim Fomenko said.

Grevtsov who studied the area in detail noticed that though the Ust-Taseyevsky stone idol is the most visible and striking today was not the main figure in the complex.

The central character worshipped by the people of the past is in the middle of the composition, above all other stones. It has one eye, a nose, and something looking like a beard.

There is disagreement about what it shows: some see the face of a man, others an animal, perhaps even a bird, most likely a raven. It is surmised that the idol that is prominent today was a ‘helper’ and probably not the recipient of ancient offerings.

Next to the helper, there is a round-shaped rock which researchers refer to as the ‘helper’s wife’.

The carving table is to the left of the helper and his wife. Behind the main sculpture, there is a ‘guard’ – the biggest rock of all on the site – whose role was seen to be to overlook the ritual site. After each of the rituals, the offerings were hidden in niches between the rocks and piled on top of the remnants of the previous offerings.

The ‘guard’ stone stood by the richest of the niches that had the most intriguing finds.

See also: Siberian Shigir Idol With Seven Faces Is The World’s Oldest Wooden Sculpture

Interestingly, the hierarchy of how the idols were set on the site is similar to the ways of the Khanty and Mansi peoples, whose geographical location is some 2,000 kilometers to the northeast. Their idols were made of wood but the order they were arranged was similar – the main idol was in the middle, a helper and his wife were to the left, a guard was to the right.

These stone figures remind us of the fascinating “Polovtsian statues” that can be found in large numbers across Russia, southern Siberia, eastern Ukraine, Germany, Central Asia, and Mongolia.

Many of the Polovtsian statues represent male warriors wearing helmets, armor, and weapons, like swords, bows, quivers. Hats and purses can be seen on the female statues.

Standing silently for all these years, these stone statues do have interesting to tell about our past.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer