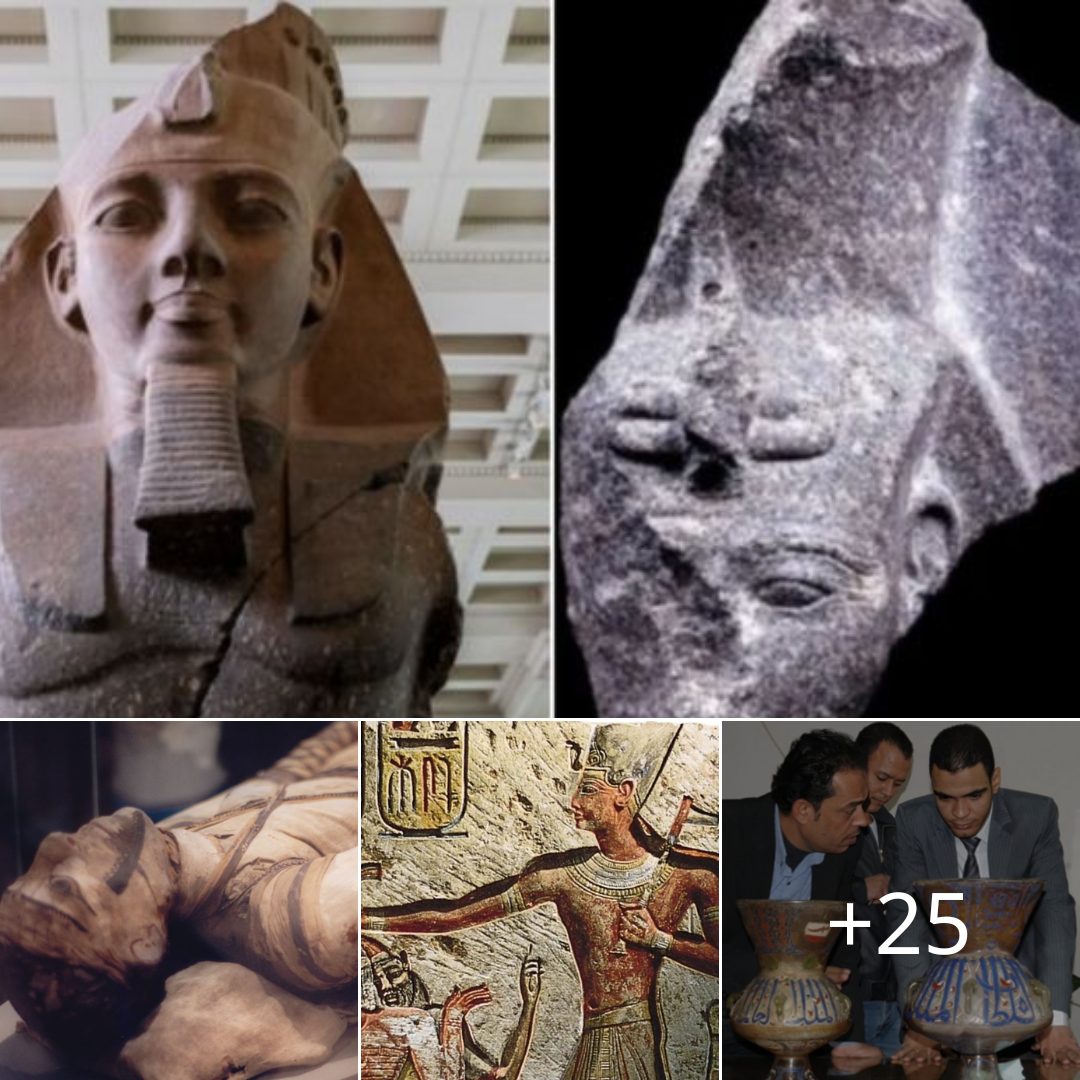

A statue of Medusa’s head was discovered at Antiochia ad Cragum in Turkey, dating to the first century. (Image credit: Michael Hoff, Hixson-Lied professor of art history, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.)

In the ruins of a Roman city in southern Turkey, archaeologists have discovered a marble head of Medusa, somehow spared during an early Christian campaign against pagan art.

The head was unearthed at Antiochia ad Cragum, a city founded during the first century, around the rule of Emperor Nero, that has all the marks of a Roman outpost —bathhouses, shops, colonnaded streets, mosaics and a local council house.

With serpents for hair, wide eyes and an open mouth, Medusa was a mythical monster who could turn a person to stone with her gaze. At Antiochia, a Medusa architectural sculpture would have served an apotropaic function, intended to avert evil —but later, her likeness would have been considered idolatrous by the Christians who came to live at the site.

“The people living at Antiochia later were zealous Christians who were destroying art in much the same way that ISIS is destroying remnants of the ancient past,” Michael Hoff, a University of Nebraska–Lincoln art historian and director of the excavations, told Live Science. “These things were meant to be destroyed and put into a lime kiln to be burned and turned into mortar.” [See Photos of the Medusa Head and Ancient Antiochia Site]

Antiochia, which covers more than 7 acres (3 hectares), is located on the sparsely populated outskirts of the town ofGazipaş, atop craggy cliffs in an area that is today dominated by wheat fields. Little is known about the city from ancient sources, and though the archaeological site had been identified in the early 19th century, it had never been given much attention by scholars until recently, Hoff said.

“The fact that it’s somewhat of an unknown city makes it fascinating for us as archaeologists,” he added. The evidence Hoff and his colleagues have dug up so far suggests Antiochia might have actually been an economic player during the Roman Empire, a center for the trade and production of wine, agriculture and glass.

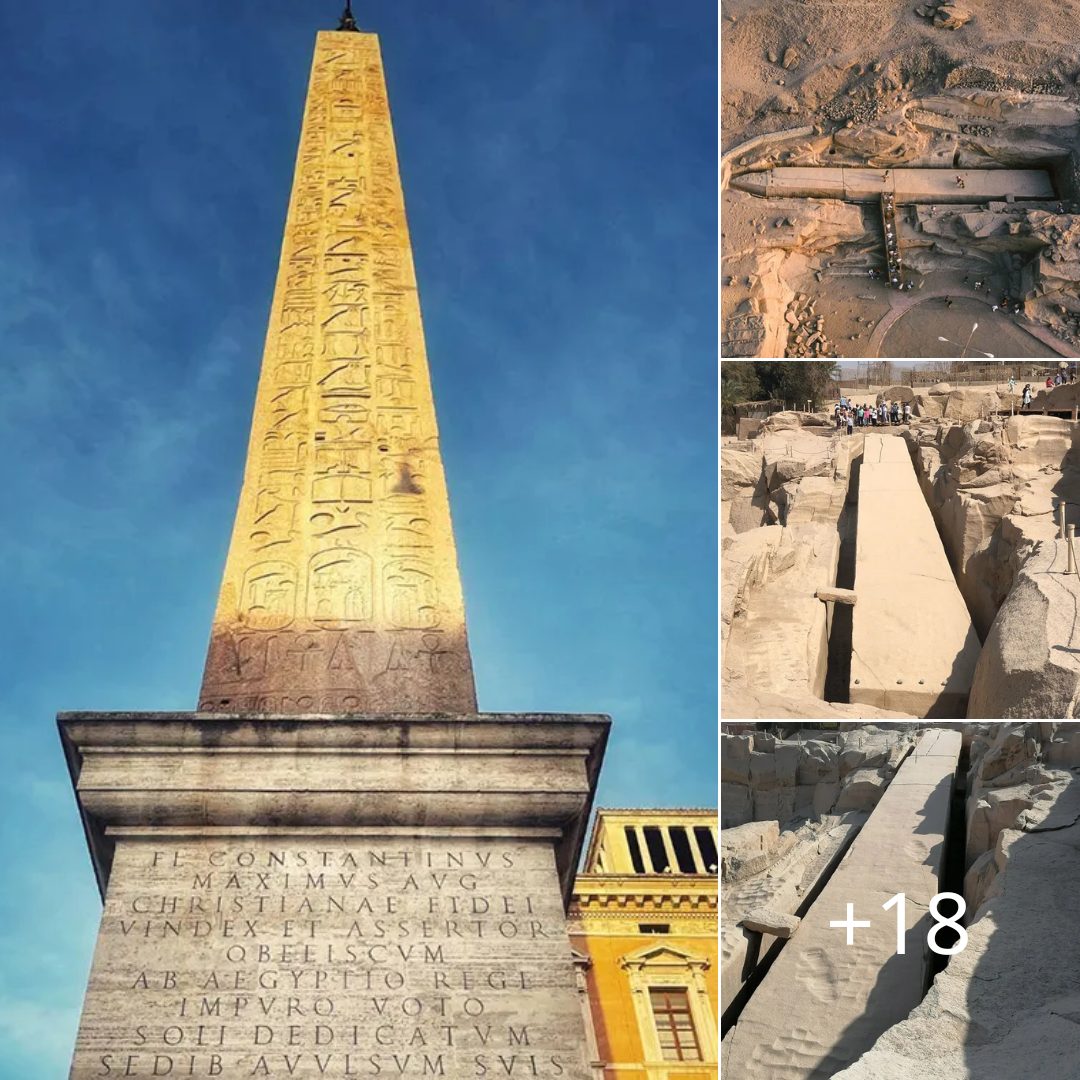

An aerial view of the bouletarian, or city council house, recently discovered at the ancient site of Antiochia ad Cragum. (Image credit: Michael Hoff, Hixson-Lied professor of art history, University of Nebraska-Lincoln)

“The result of all this economic activity is a pretty high degree of cultural output,” Hoff said. In 2012, they discovered an enormous poolside mosaic covering 1,600 square feet (150 square meters) with intricate geometric patterns. They also found the marble head of an Aphrodite sculpture in 2013.

Much of the Roman artwork from the site has been lost. Sometime after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century, several churches were built at Antiochia. Hoff said his team has found lots of broken sculptural parts and bits of statues that had smashed into pieces; they’ve also found evidence of the Christian kilns where the marble artwork would become mortar.

A group of Turkish students discovered the Medusa head near the foundations of a building that may have been a small temple. Hoff and his colleagues have reconstructed the head and other marble fragments found nearby, showing that Medusa’s head was not part of a freestanding statue, but rather it would have been incorporated into the pediment of the building.

When the team returns to the site next year, they plan to further excavate the city’s bouleuterion, the seat of the local legislature that may have doubled as a music hall or theater. Hoff said they also plan to investigate the rows of shops that line a Roman street to find out what was being sold in the marketplace.