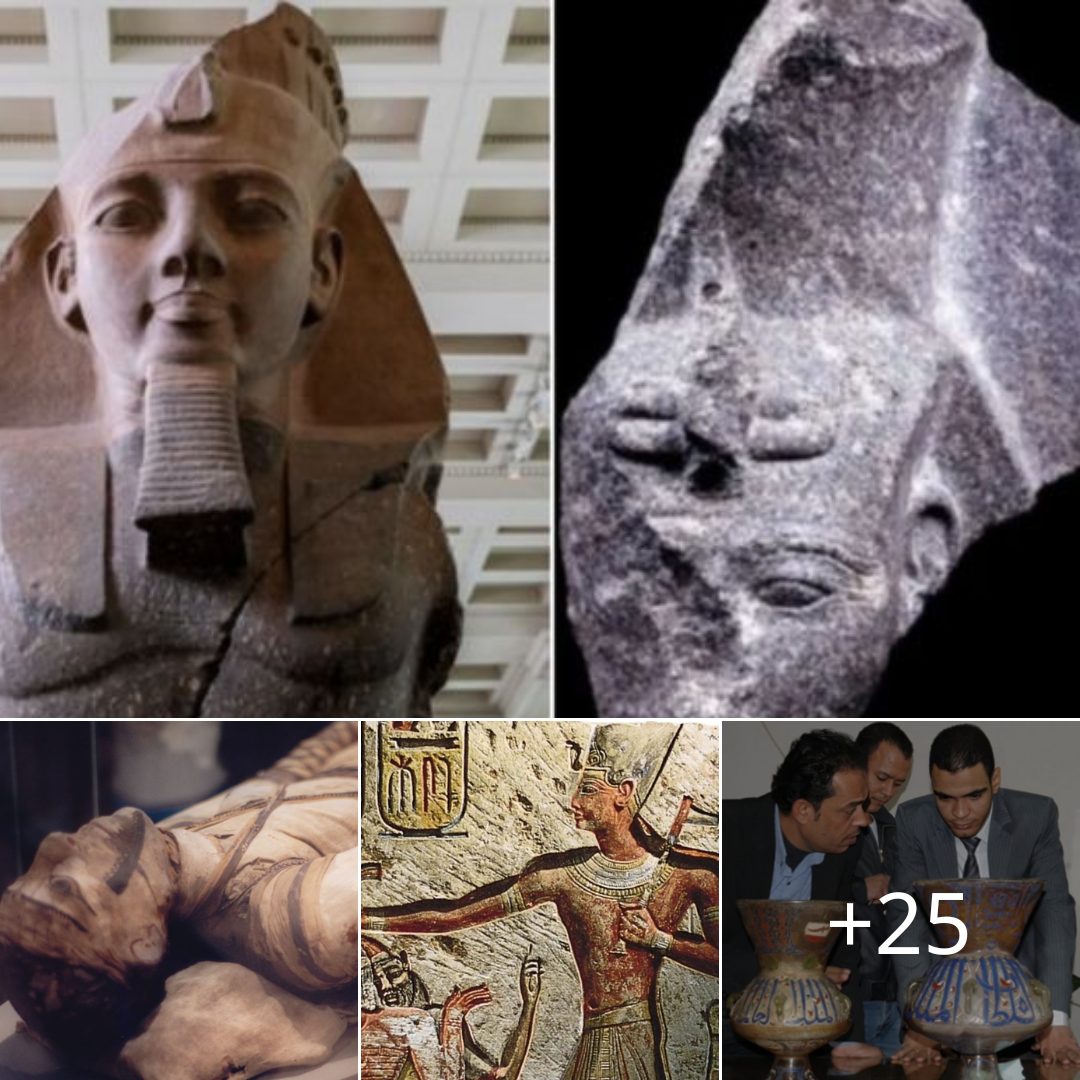

Royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings typically hold just one ruler. Built to house and protect Egyptian royalty on their journey through the after-life, these chambers carved in the rocks near modern-day Luxor were intended for a single occupant. In 1881 a tomb near Deirel-Bahri in the Theban necropolis defied these assumptions. Rather than one royal mummy, a cache of mummies was discovered there. Among the dead, scholars identified no fewer than 11 pharaohs of ancient Egypt’s splendid New Kingdom period, including Seti I, whose body was missing from his magnificent tomb, and Ramses the Great.

(How ancient Egyptians—from kings to commoners—strived for eternal life.)

Nicknamed the Royal Cache, this tomb (known to experts as TT320 or DB320) originally housed the bodies of the high priest of Amun and his family, who lived around 960 B.C. When Egyptologists documented the tomb’s contents in 1881, more than 50 bodies were found there. Many of them, like Seti I and Ramses II, were kings and queens missing from the tombs that were built for them. Although the Deir el-Bahri discovery revealed the whereabouts of these missing royals, many more were still unaccounted for. Another impressive cache would be discovered in 1898, this time in the tomb of one of Egypt’s greatest pharaohs: Amenhotep II.

THE MUMMY CACHE

ROYAL TRANSPORT

This engraving re-creates the moment in 1881 when members of the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, led by Gaston Maspero, removed mummies from the Royal Cache at Deir el-Bahri to transfer them to Cairo.MARY EVANS/CORDON PRESS. COLOR: JOSÉ LUIS RODRÍGUEZDuring the 21st Dynasty (circa 1077 B.C. to 950 B.C.), the mummies of monarchs from previous centuries were taken out of their original burial places in the Valley of the Kings and eventually hidden in a high priest’s tomb near Deir el-Bahri and in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35). Victor Loret discovered the KV35 cache less than two decades after French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero had stumbled on the mummy cache at Deir el-Bahri in 1882.Looking for kings

In 1897, Victor Loret was appointed the director of the Egyptian Antiquities Organization. The monocled Frenchman, an outstanding Egyptologist of his day, focused his energies on the nearby Valley of the Kings, the site of the subterranean tombs of many New Kingdom pharaohs.

A photograph of Victor Loret, the French Egyptologist, is from circa 1920.ALAMY/ACI

His efforts were soon rewarded. On February 12, 1898, Loret and his team discovered the tomb of Thutmose III, one of Egypt’s greatest military kings, who conquered territory as far north as Syria in the mid-15th century B.C. Like so many other royal tombs, it had been looted in antiquity. Nevertheless, some of the warrior pharaoh’s grave goods remained. Less than a month later, on March 9, those digging with Loret sighted the entrance to another tomb located at the foot of the cirque formation that surrounds the Valley of the Kings. Accompanied by a rais, the local foreman, Loret lit candles and entered.

(King Tut’s grandparents were Egypt’s royal power couple.)

In the flickering gloom, he and the rais found a small figurine among the rubble: an ushabti inscribed with the name of King Amenhotep II, son of Thutmose III. It was a tantalizing clue, but not definitive proof of the tomb owner’s identity. The entrance and the sloping passageways bored into the mountain until reaching a well, which had clearly once been filled with magnificent grave goods. Only broken remnants were left. It was obvious that this tomb, too, had been ransacked in ancient times, and Loret, disappointed, assumed that little or nothing of interest would be found.

LEFT: SUBMITTING TO THE GODS

In a pose repeated throughout ancient Egypt’s long history, this statue of Amenhotep II shows the pharaoh humbly kneeling before the gods and making an offering.ADAM EASTLAND ART + ARCHITECTURE/ALAMY

RIGHT: PHARAOH’S HELPER

This ushabti is inscribed with the names of Amenhotep II. The figure holds an ankh symbol in each hand and is wearing the nemes (royal headdress) topped with a uraeus (rearing cobra).ALAMY/ACIGoing deeper

Venturing deeper into the complex, Loret and the rais found themselves in a rectangular room supported by two pillars. In the dim light of the candles, they could make out the shape of a funerary boat. Loret was then greeted by a “horrible” sight: He wrote, “A body lay there upon the boat, all black and hideous, its grimacing face turning towards me and looking at me, its long brown hair in sparse bunches around its head.” Thieves had stripped it of its bandages and any accoutrements, leaving it bare but otherwise intact on the boat.

At the end of this room was a staircase that the two men cautiously descended. They found themselves in a short passageway that led to a vestibule. Another passageway extended beyond it to a large room with six pillars. Faint, colored murals decorated the walls on either side. The two men found and identified, with growing excitement, Amenhotep II’s name on the walls. Here then, was another piece of evidence that this place was the likely resting place of one of the New Kingdom’s most powerful rulers and builders.

An effigy of the pharaoh from the late 15th century B.C.PRISMA/ALBUM

Crunching their way over broken objects—wood, pottery, and alabaster—Loret and the rais entered a sunken area of the room, where they found a large stone sarcophagus with its lid missing. Inside was a closed coffin with a crown of dry leaves placed at the feet and flowers at the head. Given the mess the thieves had made of the tomb, was it possible that they’d left what until then no Egyptologist had managed to find—the intact mummy of a pharaoh still lying in its sarcophagus?

Loret continued his exploration of the tomb. A surprising find was three mummified bodies in one of the adjoining chambers. Closer inspection revealed their bandages had been torn away by looters, exposing bodies and faces. The tomb, however, had more surprises in store. The doorway of another adjoining chamber had been blocked with large stones. Loret lifted his candle to peer through the cracks, and by its dim light made out nine more coffins, five of them still covered with their lids.

(The gory history of Europe’s mummy-eating fad.)

SIMPLE, STRONG, AND STRIKING

This pillar, one of six dominating Amenhotep II’s burial chamber, is decorated with an image of the pharaoh receiving life from the god Osiris. The roof is decorated with stylized rows of stars, representing the night sky.KHALED DESOUKI/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGESA starry night sky covers the ceiling of the funeral chamber of KV35. Two rows of decorated pillars shows the pharaoh being received into the afterlife by the gods. Unlike other New Kingdom tombs, the art is confined to the burial chamber, and the color scheme is minimal. Historians consider the art in KV35 to be exemplary, undertaken by a highly accomplished artist.Royal remains

This pillar, one of six dominating Amenhotep II’s burial chamber, is decorated with an image of the pharaoh receiving life from the god Osiris. The roof is decorated with stylized rows of stars, representing the night sky.KHALED DESOUKI/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGESA starry night sky covers the ceiling of the funeral chamber of KV35. Two rows of decorated pillars shows the pharaoh being received into the afterlife by the gods. Unlike other New Kingdom tombs, the art is confined to the burial chamber, and the color scheme is minimal. Historians consider the art in KV35 to be exemplary, undertaken by a highly accomplished artist.Royal remains

The newly discovered tomb, later designated as tomb KV35, had outstripped all expectations. Loret later returned to begin the process of excavation and evacuation of its contents. Cotton-lined boxes were brought in to carry away the multiple mummies. Moving aside the stones obstructing the side chamber, Loret then began to investigate the nine bodies inside.

After brushing away the thick layer of dust that covered the lid of the nearest coffin, Loret read, with astonishment, the royal protocol with the name of Ramses IV. Working his way from coffin to coffin, he revealed the names of Thutmose IV, Amenhotep III, Merneptah, SetiII, Siptah, Ramses V, and Ramses VI. The ninth belonged to a woman, whose identity remains uncertain. As with the Royal Cache found at Deir el-Bahri 16 years earlier, the Frenchman had hit on a group of relocated mummies that included some of the most powerful and celebrated pharaohs of the New Kingdom.

The pharaoh’s mummy?

But if this tomb had become a secret resting place for this band of royal mummies, could Amenhotep II’s body still be here? The answer would be found in the sarcophagus in the lower level of the burial chamber. Loret had not disturbed its contents when he first encountered the coffin, but he was prepared to examine it more thoroughly now.

Loret removed the crown of leaves from the foot of the coffin and saw with horror that it had been covering a hole in the wood. Was it possible that despite everything, the thieves had in fact removed the mummy? Loret reached into the hole, but his fingers met empty space. Tense moments followed as he and his colleagues eased off the coffin’s lid. There, before him, was an intact mummy.

ROYAL REPOSE

The mummified remains of Amenhotep II rest in his sarcophagus in KV35. The mummy was moved in 1931 to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in 2021.ALAMY/ACI

The coffin was significantly longer than the body inside it, explaining why Loret’s hand (and perhaps that of an earlier looter) felt nothing at the foot end. This body would be identified as Amenhotep II, who died circa 1400 B.C. after ruling Egypt for nearly three decades.

Missing mummies

Together with the mummies found in the Deir el-Bahri cache 16 years earlier, the bodies found at KV35 accounted for nearly all the 18th dynasty pharaohs (circa 1549 B.C. to 1292 B.C.), as well as several from the 19th and 20th dynasties. The latter dynasty concluded with the reign of Ramses XI around 1077 B.C.

(Was this woman Egypt’s first female pharaoh?)

The practice of using preexisting tombs to safeguard older royal mummies began during a period of decline in the 21st dynasty (circa 1077 B.C. to 950 B.C.). Egyptologists noted that tombs where the pharaohs had originally rested were being looted then. In an attempt to protect their ancestors, the priests of the 21st dynasty repurposed the Deir el-Bahri tomb, which had been built for a high priest. When the cache at Deir el-Bahri reached capacity, KV35 then became the next one. The choice was evidently a good one: Egypt’s mightiest kings slumbered there undisturbed until Loret entered with his candle in 1898.

Treasures in the tomb

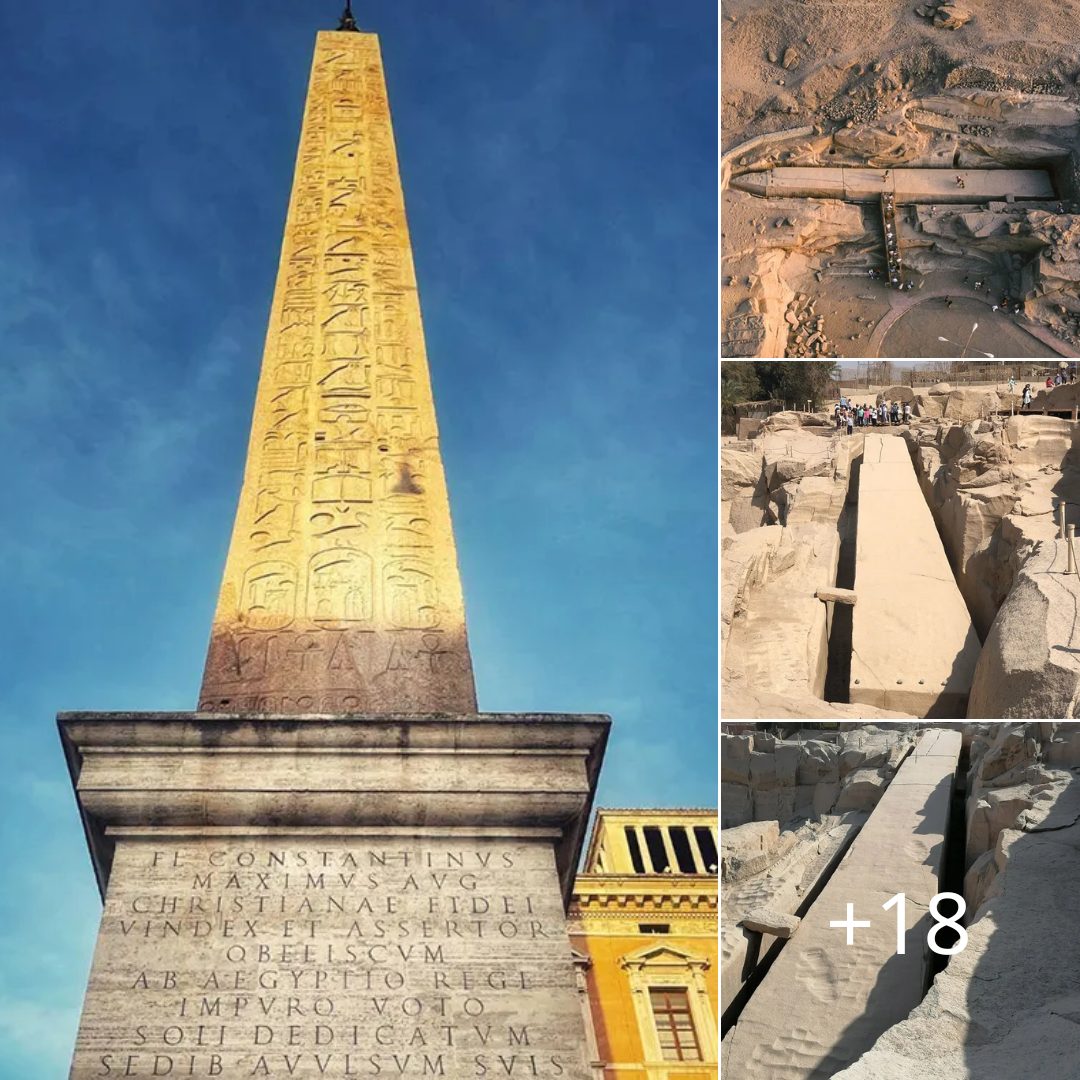

1 / 4Some 300 feet in length, tomb KV35 has the typical L-shape of royal tombs built during the 18th dynasty. It is one of the deepest structures in the Valley of the Kings. Objects like these amulets, all produced in the 15th century B.C., were among Amenhotep II’s grave goods. The amulets include the ankh symbol, the <i>djed</i> pillar, and the <i>was</i> scepter.

AMULETS

Some 300 feet in length, tomb KV35 has the typical L-shape of royal tombs built during the 18th dynasty. It is one of the deepest structures in the Valley of the Kings. Objects like these amulets, all produced in the 15th century B.C., were among Amenhotep II’s grave goods. The amulets include the ankh symbol, the KENNETH GARRETT

Most of the KV35 mummies were removed from the tomb and taken to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, but Amenhotep II’s body remained in situ. In 1901 thieves broke into the tomb. They damaged the funerary barge, smashed the mummy resting on it, and stole the body of Amenhotep II. Howard Carter, the Egyptologist who would later discover King Tut’s tomb, tracked down the culprits and recovered the pharaoh’s mummy, which had been damaged during the robbery. It was returned to the sarcophagus. Only in 1931 was Amenhotep II—whose descendants would include Akhenaten and his likely son Tutankhamun, whose tomb would be discovered in 1922—taken to Cairo.

DEATH VALLEY

The Valley of the Kings, pictured here, is the final resting place of many pharaohs. Known by Egyptologists as KV35, the tomb of Amenhotep II held many royal mummies.FERNANDO ESTRADA

(How King Tut conquered pop culture.)

Family trees

While the names of many of KV35’s occupants are known, there are three mummies (two women and one young man) whose identities are the subject of great debate. The young man with a braid is widely believed to be a prince, but experts disagree on which one. Some think he is Amenhotep II’s son Prince Webensennu, while other argue that he is Thutmose, the eldest son of King Amenhotep III. Initially, Loret had assumed the mummy lying on the boat in the pillared chamber was Prince Webensennu, but to the frustration of Egyptologists, the destruction of that body in the 1901 burglary makes an ironclad identification unlikely.

Three mystery mummies

1 / 3Three of the mummies that Loret discovered in tomb KV35 had been greatly damaged in antiquity, stripped of most of their bandages and removed from their coffins. The thieves broke the bodies open to extract funerary amulets, which were often made of gold and precious stones. Scholars had competing theories about their identities but little hard evidence until recently, when DNA analysis offered more clues, like for the so-called Elder Lady. Today the woman with long hair is believed to be Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III, grandmother of Tutankhamun, and mother to the Younger Lady.Three of the mummies that Loret discovered in tomb KV35 had been greatly damaged in antiquity, stripped of most of their bandages and removed from their coffins. The thieves broke the bodies open to extract funerary amulets, which were often made of gold and precious stones. Scholars had competing theories about their identities but little hard evidence until recently, when DNA analysis offered more clues, like for the so-called Elder Lady. Today the woman with long hair is believed to be Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III, grandmother of Tutankhamun, and mother to the Younger Lady.BRIDGEMAN/ACI

One of the female mummies was first identified as male by Loret because of its shaved head, only later confirmed as being female. Now she is commonly known as the Younger Lady. British Egyptologist Joann Fletcher suggested in 2003 that she was Nefertiti, but in 2010 DNA testing showed that the Younger Lady is King Tutankhamun’s mother, whose name is still unknown.

The third mummy, known as the Elder Lady, has long flowing hair, a useful clue in determining her identity. A lock of hair was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, in small nested coffins bearing the name of Tut’s likely grandmother, Queen Tiye, the great royal wife of Amenhotep III. Analysis found that the hair sample from the Elder Lady matches the hair in Tut’s tomb, and in 2010 DNA testing confirmed the results, restoring Queen Tiye’s name to her mummy, which now rests in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

WHO IS THE YOUNGER LADY?

Zahi Hawass examines the mummy of the Younger Lady in 2010.KENNETH GARRETTA major study undertaken in 2010 to establish ancestral links among royal mummies of the 18th dynasty included one of the KV35 mummies. Known as the Younger Lady, she is the subject of many fascinating notions about her identity—from Nefertiti to Kiya, another of Akhenaten’s wives—but none are conclusive. The study, undertaken by Egyptian scholar Zahi Hawass, used DNA analysis to show the Younger Lady is the full sister of Pharaoh Akhenaten and the mother of his successor, Tutankhamun. Her name remains elusive and has not been found among the grave goods of her famous son. Some speculate that she may have died when Tutankhamun was still an infant, before he became king in circa 1332 B.C., at age eight or nine.

Howard Carter’s 1922 discovery of the intact tomb of Tutankhamun is often hailed as the greatest of all Egyptian discoveries. But the complex, interlocking family relationships between the boy king and his ancestors was better understood thanks to the huge amount of information revealed by Loret’s find at KV35 and the discovery at Deir el-Bahri. Taken together, the successive discoveries in Egypt in the late 1800s and early 1900s helped flesh out the lives and relationships of the powerful royal protagonists of that distant time.