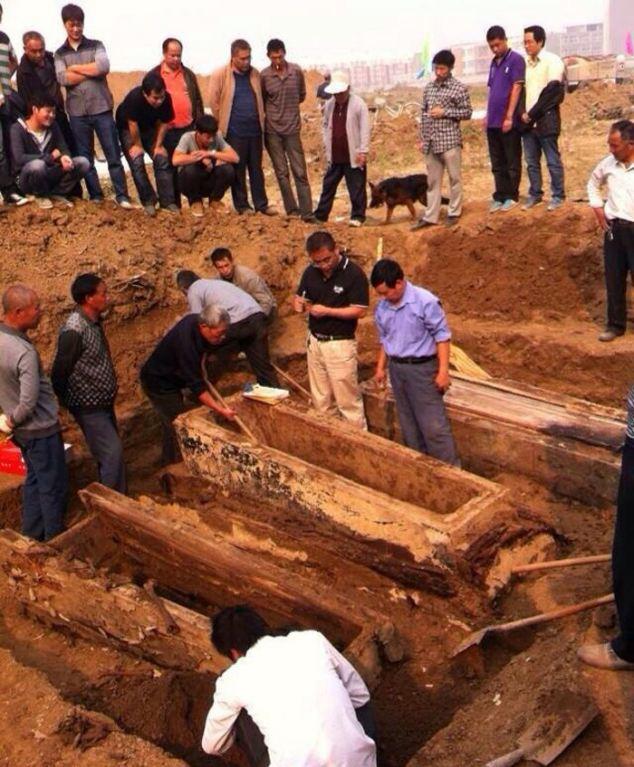

Un barco de guerra de 300 años de edad, en el que dos bodas fueron reducidas a esqueletos mientras una estaba perfectamente preservada, ha desconcertado a los arqueólogos chinos.

Cuando una de las cofias fue abierta, la cara del hombre, expertos afirman, estaba perfectamente preservada. En horas, sin embargo, la cara empezó a volverse negra y un olor fétido emanó del cuerpo.

La piel en los cuerpos, que ahora ha sido llevada a la universidad local para su estudio, también se ha tornado negra. El cuerpo se cree que pertenece a la dinastía Qin. Fue descubierto el 10 de octubre en un sitio de construcción en un hueco subterráneo de dos metros de profundidad en el terreno agrícola en la provincia de Hubei, centro de China.

La Dra. Luks Nickel, especialista en arte y arqueología china en la Escuela de Estudios Orientales y Africanos de la Universidad de Londres, le dijo a MailOnline que las preservaciones como estas no son intencionales. “Los chinos no hacen ningún tratamiento del cuerpo para preservarlo como se conoce en la antigua Egipto, por ejemplo”, explicó.

Sin embargo, intentaron proteger el cuerpo colocándolo dentro de ataúdes de cobre y sellándolo con cera. Así que la integridad física del cuerpo era importante para ellos. En la antigua China, al menos, se esperaba que los difuntos permanecieran en el cuerpo durante el entierro. Ocasionalmente, los cuerpos en la dinastía Qin eran preservados por las condiciones naturales que se encontraban dentro del ataúd.

En este caso, el cuerpo puede haber tenido un ataúd lacado, común en ese momento. Esto significa que la superficie del cuerpo habría sido inusualmente suave al tacto. La Dra. Nickel agregó que si este fuera el caso y, tan pronto como el aire golpeara el cuerpo, el proceso natural se activaría rápidamente y el cuerpo se desintegraría en poco tiempo.

Cuando el ataúd fue abierto por historiadores en Xi’an, se observó que la cara del hombre estaba casi normal, pero dentro de horas se empezó a poner negra y se desintegró rápidamente. El historiador Dong Hsiung dijo: “La ropa en el cuerpo indica que era una figura muy importante de la antigua dinastía Qin. Lo sorprendente es cómo el tiempo parece atrapado en los cuerpos, incluso después de años en un día”.

From 1644 to 1912, the Qing Dynasty succeeded the Ming Dynasty and was the last imperial dynasty of China before the creation of the Republic of China. Under the Qing’s territorial expansion, the empire grew to three times its size and the population increased from around 150 million to 450 million.

The present-day boundaries of China are largely based on the territorial control exerted by the Qing Dynasty. Burial rituals in the Qing Dynasty were the responsibility of officials. Provincial officials were assigned an alternate throne room, where the deceased almost seemed to preserve the body. Professor Dong proposed an alternative theory for preservation.

“It’s possible the man’s family used some materials to preserve the body,” he said. “Once it was opened, the natural process of decay could really start.” “We are working hard to save what there is.”

Historian Dong Xiang said, “The clothes on the body indicate he was a very senior official from the early Qing Dynasty. What is amazing is the way time seems to be catching up on the corpse, aging hundreds of years in a day.”

The Qing Dynasty, as well as the preceding Ming Dynasty, are known for their well-preserved corpses. In 2011, a 700-year-old mummy was discovered in excellent condition in eastern China. The corpse of the high-ranking woman believed to be from the Ming Dynasty was stumbled upon by a team who were looking to expand a street.

Discovered two meters below the road surface, the woman’s features—from her head to her shoes—retained their original condition and hardly deteriorated. The mummy was wearing traditional Ming Dynasty costume and in the coffin were bronze mirrors, ceramics, ancient writings, and other relics.

Wang Weiyin, the curator of the Museum of Taizhou, stated that the mummy’s clothes were mainly made of silk, with a small amount of cotton. Researchers hope that the findings could help them understand the final rituals and customs of the Qing Dynasty, as well as more about how bodies were preserved.